Discovering Uncle Keith

When a family discover a 1944 pocket diary, inscribed in tiny writing with scattered dates circled in blue ink, they begin to piece together the untold story of their ‘Uncle Keith’ who once fell from a window and then later died mysteriously at the age of 40. Here Felice Hawley describes how the family finally got to know and understand her husband, Jonathan Thomas’s late Uncle Keith and his struggle with epilepsy.

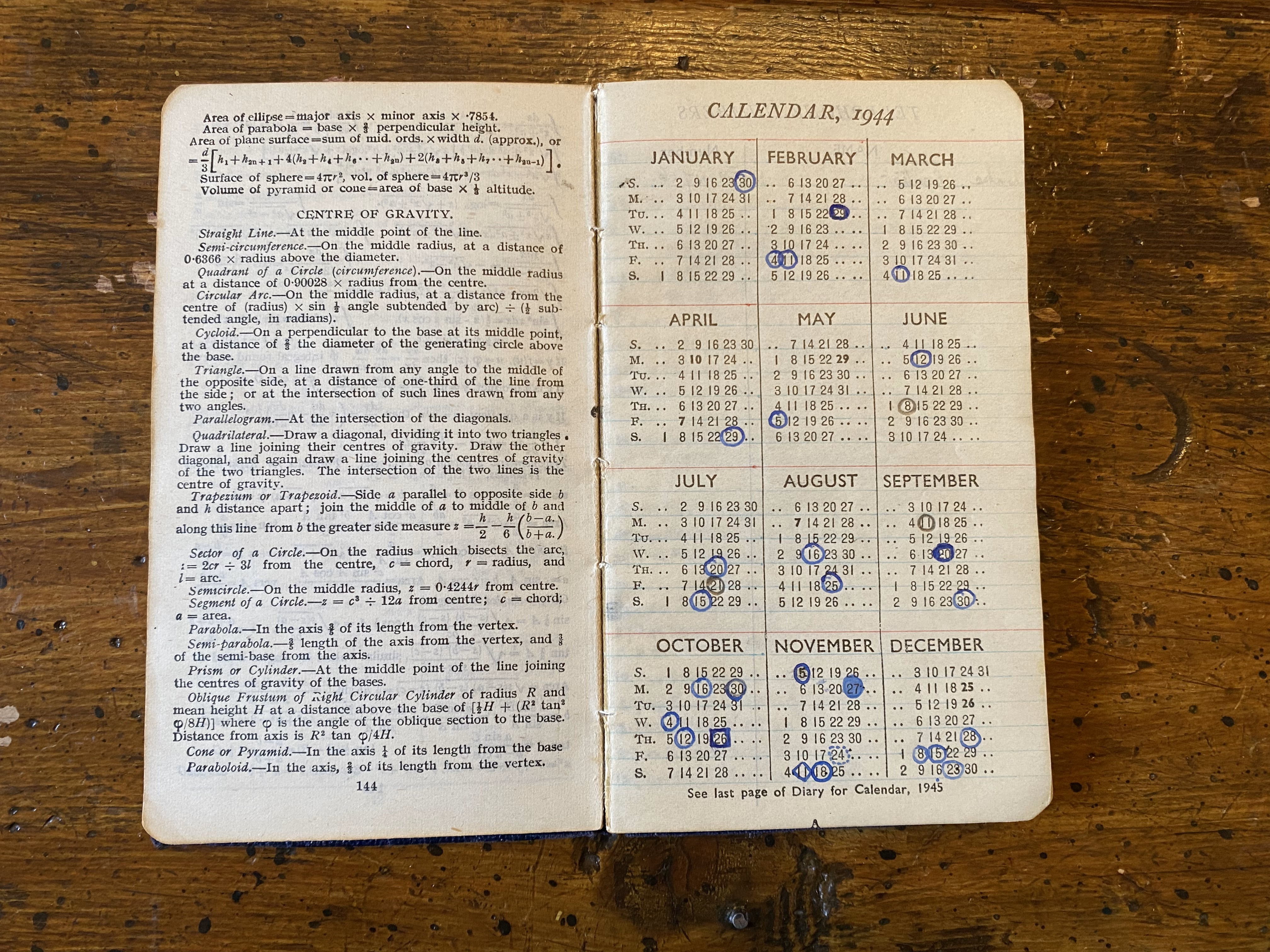

The 1944 diary

Keith, pictured in his Army Cadet Force uniform, lives a fairly typical teenage life in 1944 Britain. He plays billiards and table tennis at the Youth Club with his friends, eats in Civic Cafés and goes to the “flicks” at least twice a month. He gets a certificate from the Army Cadets. His family home is damaged during air raids.

He follows events in the war closely and even counts the number of V1 flying bombs he sees. He’s proud of his big brother Hugh, a Lancaster pilot who earns a DFC that year, although he’s a little jealous of Hugh’s girlfriend Joan. And, like many 17-year-olds, he chafes at his mother’s protectiveness.

But Keith is not like most of his contemporaries. A year or two earlier he had been diagnosed with epilepsy.

This part of Keith’s life comes to light decades later when his nephews find a blue Collins ‘Aero’ pocket diary for 1944 in their parents’ house. Although the tiny writing filling each day’s entry is not familiar, it doesn’t take long to spot that the person writing about ‘Hugh’, ‘Joan’ and ‘Mum’ and the events of 1944 must be Keith.

Discovering Keith

Keith was born in Horsham, Sussex in 1926. He was 10 and his older brother Hugh was 15 when their father died and their mother set up a boarding house in Surbiton to support her family. Keith was still living there with her when she died in 1964.

His younger nephew Jonathan didn’t know much more about ‘Uncle Keith’s’ life other than that he was not married, had no children and had spent time in hospital after falling from a window. He didn’t know what caused Keith’s early death at 40 in 1966.

At first, the diary raised questions, rather than answered them. Why was Keith not in school or heading to the military when he turned 18 in September? What pills was he seeing the doctor about? And why did he get fired on his very first day at British Thermostat?

One clue eventually helped to explain it all. Scattered dates are circled on the diary’s full year calendar page, one to five in blue ink every month. (Three black circles mark family birthdays.) Oddly resembling a woman tracking her monthly cycle, they actually line up with a phrase Keith repeats on different days - “had a fit”. In between news of the war, his job and family events, Keith is tracking his epileptic seizures.

Keith never uses the word ‘epilepsy’ in the diary, yet his descriptions show what he has to deal with day to day because of his condition. He worries about ‘telling’ people, including his new boss and a girl he fancies. After getting fired from British Thermostat - likely because they discovered his condition - he gets a job as an agricultural labourer for the Municipal Borough of Malden and Coombe. He’s excited about learning to drive a tractor, but is soon banned after a seizure and is only allowed to lead the plough horse. He has to check if his seizure medication will interfere with dental pain killers.

It's possible to feel his embarrassment as his seizures become more frequent and more severe, especially when they start happening at work. Keith regularly complains about being “dreamy” or even “very dreamy” which sometimes scares his colleagues.

And while family and friends are serving in the war, he fails his conscription medical – as he clearly knows he would.

In the diary Keith mentions several appointments with his local GP Dr James Stott, who is also Director of Medical Staff at Surbiton Hospital. And Keith writes about going up to St Thomas’s Hospital in London. “A Dr. Maybury looked after me. There may be a chance of keeping it under – but only may!” Whatever that treatment, it doesn’t stop his ‘fits’. They go from a single seizure in January to four or five a month by the end of the year.

After 1944

If Keith kept other diaries, they didn’t survive to explain what happened before 1944 or over the next 22 years. But a packet of letters and newspaper cuttings discovered later helped fill the gaps.

Hugh, pictured below, writes to a social worker that “petit mal was observed in Keith at least by the age of three or four but the first grand mal was not until he was about 16.”

Then an article from late 1966 in the Bucks Free Press describes the inquest into Keith’s death: “Quiet Man’s Mystery Fall From Tower”. The coroner determined that Keith had ‘slipped or jumped’ from the 54ft water tower at Chafont St Peter. It was the first time his nephew Jonathan knew his uncle had epilepsy and that his death may not have been natural.

At the inquest, Hugh testified that for the previous eight years his brother had been treated at a series of mental hospitals where there may have been other suicide attempts. In spring 1966 the welfare officer at Longrove (Mental) Hospital in Epsom wrote to say that although Keith had improved enough to be discharged, she did not believe he could live on his own.

Hugh persuaded a reluctant Keith to move to Chalfont voluntarily, rather than under an Order of Protection. He seemed to settle in well and enjoy his work in the dairy – a Charge Nurse told the inquest he was “quiet and well-behaved” – but two months later he was dead.

The coroner later recorded an open verdict – Keith left no note.

Find out more

Keith’s 1944 diary is being published day-by-day, along with extracts of Hugh’s letters, on Facebook – search for ‘Wartime Brothers 1944’. There’s also a blog at wartimebrothers.com