On This Page

- An introduction to epileptic seizures

- Are all seizures the same?

- Why do epileptic seizures happen?

- Some facts about seizures

- Types of seizures

- What are focal seizures?

- Levels of consciousness

- What happens during focal seizures?

- What are generalised seizures?

- What are unknown seizures?

- What are unclassified seizures?

- What should I do if someone has a seizure?

An introduction to epileptic seizures

Any of us could potentially have a single seizure at some point in our lives. This is not the same as having epilepsy, which is a tendency to have seizures that start in the brain.

This information covers different types of epileptic seizures and what they can look like. Whether you, or someone you know, has had a single seizure or has been diagnosed with epilepsy, it may help to identify the type of seizures that are relevant to you, and how they affect you. Also, below there is information on what to do if someone has

a seizure. Call our helpline for information or time to talk.

Are all seizures the same?

Epileptic seizures start in the brain. There are other types of seizures which may look like epileptic seizures but they do not start in the brain. Some seizures are caused by conditions such as low blood sugar (hypoglycaemia) or a change to the way the heart is working. Some very young children have ‘febrile convulsions’ (jerking movements) when they have a high temperature. These are not the same as epileptic seizures. In this information when we use the word ‘seizure’ we mean an epileptic seizure.

Why do epileptic seizures happen?

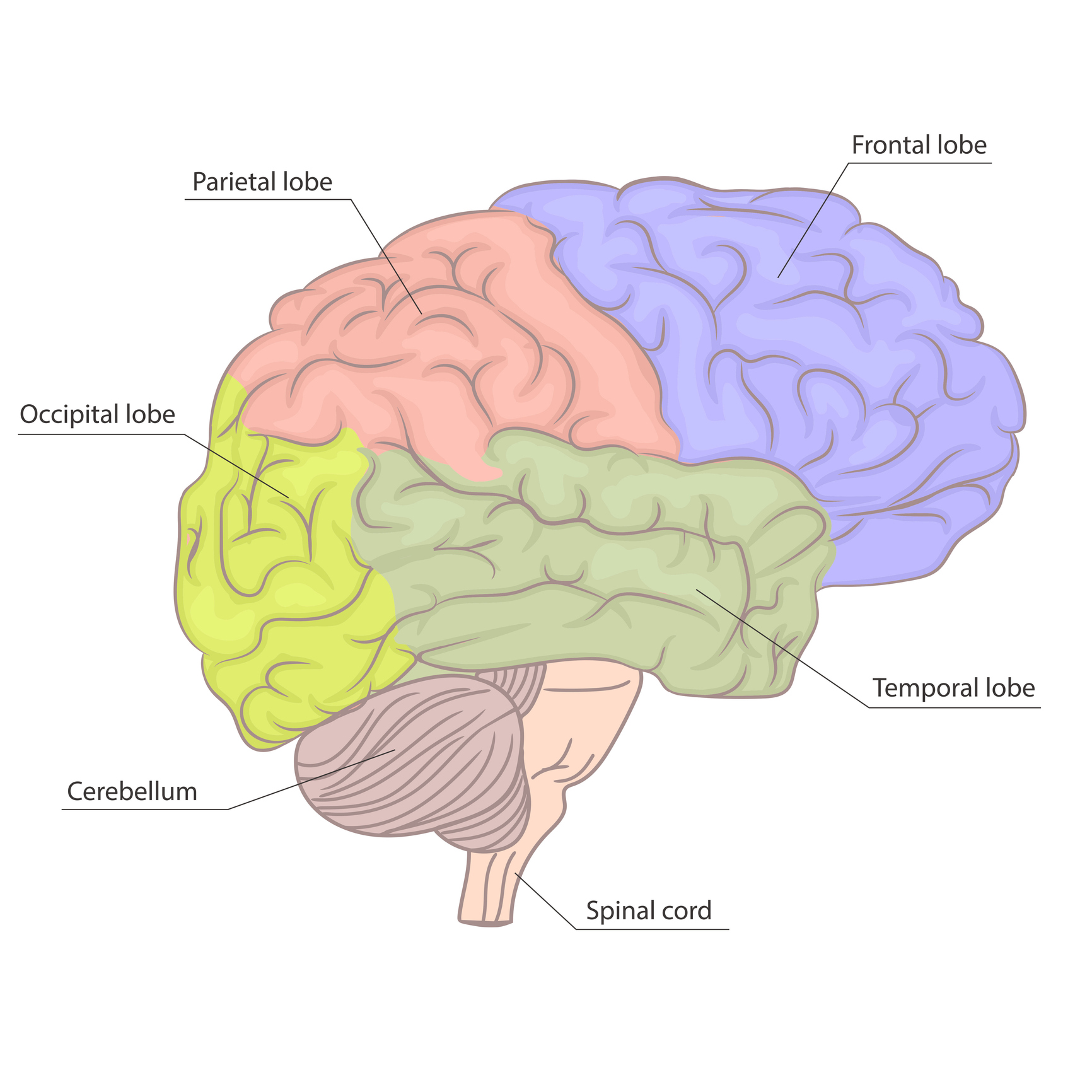

The brain has millions of nerve cells which control the way we think, move, and feel. The nerve cells do this by passing electrical signals to each other. If these signals are disrupted, or too many signals are sent at once, this causes a seizure. The brain has many different functions. Mood, memory, movement, consciousness, and our senses are all controlled by the brain, and any of these can be affected if someone has a seizure. They may feel strange or confused, behave in an unusual way, or lose some or all awareness during the seizure. The brain has two sides called hemispheres. Each hemisphere has four parts called lobes. Each lobe is responsible for different things such as vision, speech, and emotions.

One hemisphere of the brain (side-view)

Some facts about seizures

- Most seizures happen suddenly without warning, last a short time (a few seconds or minutes), and stop by themselves.

- Seizures can be different for each person.

- Just knowing that someone has epilepsy does not tell you what their epilepsy is like, or what type of seizures they have.

- Calling seizures ‘major’ or ‘minor’ does not tell you what happens to the person during a seizure. The names of seizures used in this information describe what happens in a seizure.

- Some people have more than one type of seizure, or their seizures may not fit clearly into the types described here. But even if someone’s seizures are unique, they usually follow the same pattern each time they happen.

- Not all seizures involve jerking or shaking movements. Some people seem vacant, wander around, or are confused during a seizure.

- Some people have seizures when they are awake, called ‘awake seizures’. Some people have seizures while they are asleep, called ‘asleep seizures’ (or ‘nocturnal seizures’). The names ‘awake’ and ‘asleep’ do not explain the type of seizures, only when they happen.

- Injuries can happen during seizures, but many people don’t hurt themselves, and don’t need to go to hospital or see a doctor.

See our information on first aid.

Types of seizures

In March 2017 the International League Against Epilepsy (ILAE), a group of the world’s leading epilepsy professionals, introduced a new method to group seizures, which they called a ‘classification’. This gives doctors a more accurate way to describe a person’s seizures, and helps them to prescribe the most appropriate treatments. In April 2025 they updated their classification.

Seizures are divided into groups depending on:

• how much of the brain is affected;

• whether or not a person loses consciousness; and

• whether or not seizures involve other symptoms, that you can see or hear.

Depending on where they start, seizures are described as focal, generalised, unknown, or unclassified. Some seizures involve symptoms that you can see or hear, such as movement, noises, or looking flushed. ILAE calls these ‘observable manifestations’. Other seizures involve symptoms that can’t be seen or heard, such as unusual feelings or sensations. These are described as ‘without observable manifestations’.

What are focal seizures?

Focal seizures start in, and affect, just one part of the brain, sometimes called the ‘focus’ of the seizures. They might affect a large part of one hemisphere or just a small area in one of the lobes. Sometimes a focal seizure can spread to both sides of the brain (bilateral). Some people view this focal seizure as a warning, that another seizure will happen. See focal to bilateral tonic-clonic seizures, below.

Levels of consciousness

Focal seizures are also described depending on a person’s consciousness during their seizures – whether or not they are aware of what is happening around them and if they are able to respond.

Focal preserved consciousness seizures

In focal preserved consciousness (previously called focal aware seizures) the person is conscious, will usually know that something is happening and can respond and will remember the seizure afterwards. Some people find it hard to put their focal preserved consciousness seizures into words. During the seizure, they may feel ‘strange’ but not be able to describe the feeling afterwards. This may be upsetting or frustrating for them.

Focal impaired consciousness seizures

Focal impaired consciousness seizures (previously called focal impaired awareness seizures) affect a bigger part of one hemisphere (side) of the brain than focal preserved consciousness seizures.

The person’s consciousness is affected and they may be confused. They might be able to hear you, but not fully understand what you say or be able to respond to you. They may not react as they would normally. If you speak loudly to them, they may think you are being aggressive, and so they may react aggressively towards you.

Focal impaired consciousness seizures often happen in the temporal lobes but can happen in other parts of the brain.

After the seizure, the person may be confused for a while. This is sometimes called ‘post-ictal’ (after-seizure) confusion.

It may be hard to tell when the seizure has ended. The person might be tired, and want to rest. They may not remember the seizure afterwards.

What happens during focal seizures?

This depends on where in the brain the seizure happens and what that part of the brain normally does.

Seizures with observable manifestations can involve:

• making lip-smacking or chewing movements, repeatedly picking up objects or pulling at clothes;

• suddenly losing muscle tone and limbs going limp or floppy, or limbs suddenly becoming stiff;

• repetitive jerking movements that affect one or both sides of the body;

• stiffness or twitching in part of the body, (such as an arm or hand);

• making a loud cry or scream; or

• making strange postures or repetitive movements such as cycling or kicking.

Seizures without observable manifestations can involve:

- a ‘rising’ feeling in the stomach or déjà vu (feeling like you’ve ‘been here before’);

- getting an unusual smell or taste;

- a sudden intense feeling of fear or joy;

- a strange feeling like a ‘wave’ going through the head;

- a feeling of numbness or tingling;

- a sensation that an arm or leg feels bigger or smaller than it actually is; or

- visual disturbances such as coloured or flashing lights or hallucinations (seeing something that isn’t actually there).

Focal to bilateral tonic-clonic seizures

Sometimes focal seizures spread from one side to both sides of the brain. This is called a focal to bilateral tonic-clonic seizure (previously called a secondarily generalised tonic clonic seizure). When this happens the person becomes unconscious and will usually have a tonic clonic (jerking or shaking) seizure. When focal seizures spread very quickly, the person may not be aware that it started as a focal seizure.

What are generalised seizures?

Generalised seizures affect both sides of the brain at once and happen without warning. The person will be unconscious (except in myoclonic seizures), even if just for a few seconds, and afterwards will not remember what happened during the seizure.

Tonic clonic seizures

These are the seizures most people think of as epilepsy.

At the start of the seizure:

- the person becomes unconscious;

- their body goes stiff, and if they are standing up they usually fall backwards;

- they may cry out; and

- they may bite their tongue or cheek.

During the seizure:

- they jerk and shake as their muscles relax and tighten rhythmically;

- their breathing might be affected and become difficult or sound noisy;

- their skin may change colour and become very pale or bluish; and

- they may wet themselves.

After the seizure (once the jerking stops):

- breathing and colour usually returns to normal; and

- they may feel tired, confused, have a headache, or want to sleep.

A person’s seizures usually last the same length of time each time they happen, and stop by themselves. However, sometimes seizures do not stop, or one seizure follows another without the person recovering in between. If this goes on for five minutes or more it is called status epilepticus, or ‘status’. Status is not common, but can happen in any type of seizure and the person may need to see a doctor. Status in a tonic clonic seizure is a medical emergency, and the person will need urgent medical help. It is important to call for an ambulance. See below for what to do if someone has a seizure.

Clonic seizures

Clonic seizures involve repeated rhythmical jerking movements of one side or part of the body or both sides (the whole body) depending on where the seizure starts. Seizures can start in one part of the brain (focal with observable manifestations) or affect both sides of the brain (generalised clonic).

Tonic and atonic seizures

In a tonic seizure the person’s muscles suddenly become stiff. If they are standing they often fall, usually backwards, and may injure the back of their head. Tonic seizures tend to be brief and happen without warning. In an atonic seizure (or ‘drop attack’) the person’s muscles suddenly relax, and they become floppy. If they are standing they often fall, usually forwards, and may injure the front of their head or face. Like tonic seizures, atonic seizures tend to be brief and happen without warning. With both tonic and atonic seizures people usually recover quickly, apart from possible injuries.

Myoclonic seizures

Myoclonic means ‘muscle jerk’. Muscle jerks are not always due to epilepsy (for example, some people have them as they fall asleep). Myoclonic seizures are brief but can happen in clusters (many happening close together in time), and often happen shortly after waking.

In myoclonic seizures the person is conscious, but they can be classified as focal or as generalised seizures. This is because they may be followed by a generalised seizure (such as a tonic clonic seizure).

Negative myoclonic seizures

In this type of seizure, the person briefly loses muscle tone and may lose their balance and fall or struggle to regain their balance. They may lose their grip on objects and drop them. Negative myoclonic seizures can sometimes be a symptom of an epilepsy syndrome.

Absence seizures

Absence seizures are more common in children than in adults, and can happen very frequently.

Typical absences

During a typical absence the person becomes blank and unresponsive for a few seconds. They may appear to be ‘daydreaming’. The seizures may not be noticed because they are brief. The person may stop what they are doing, look blank and stare, or their eyelids might blink or flutter. They will not respond to what is happening around them. If they are walking they may carry on walking, but will not be aware of what they are doing.

Atypical absences

Atypical absences are similar to typical absences (see above) but they start and end more slowly, and last a bit longer than typical absences. As they also include a change in muscle tone, where the limbs go limp or floppy, some people may fall.

What are unknown seizures?

This term is sometimes used to describe a seizure if doctors are not sure where in the brain the seizure starts. This may happen if the person was asleep, alone, or the seizure was not witnessed.

What are unclassified seizures?

If there is not enough information about a person’s seizure, or if it is unusual, doctors may call it an unclassified seizure. See our information on recording seizures.

What should I do if someone has a seizure?

How you can help someone during a seizure will depend on the type of seizures they have, and how much you know about their epilepsy. If you don’t know the person follow our basic first aid message:

- Calm

Stay calm and take control of the situation - Cushion

Cushion their head with something soft - Call

Call an ambulance

If they seem confused, stay with them, talk calmly and quietly, and gently guide them away from any danger.

For more detailed information visit our first aid page.

Epilepsy Society is grateful to Dr F J Rugg-Gunn, Consultant Neurologist & Honorary Associate Professor Clinical Lead, Chalfont Centre for Epilepsy, who reviewed this information.

Information updated: June 2025. Review date: 2027.

Download this information

For a printed copy contact our Helpline.